Takara SF Land Evolution

Updated Diaclone (2016) on 1 September

Takara SF Land celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2022. The umbrella term used by fans to describe various toylines with sci-fi elements sold by Takara (Takara Tomy after the 2006 merger with Tomy), Takara SF Land encompasses lines like Henshin Cyborg (a 30cm-tall figure that could transform into other characters and into a vehicle), the groundbreaking Microman (10cm-tall action figures with stunning articulation for 1974) and the Diaclone robots and vehicles piloted by 3cm-tall figures with magnetic feet.

Takara SF Land toys are notable for being original designs as opposed to being inspired by popular manga, anime or tokusatsu series. If some of the resulting toys were stand out designs far ahead of their time, it’s simply because they needed to be — they couldn’t rely on brand recognition as a crutch.

There were, of course, toy-first Takara designs that benefitted immensely from the exposure manga and anime tie-ins provided. The Magne Robo Koutetsu Jeeg figure, for example, certainly got a boost from the Nagai Go manga and the Toei anime but the toy, competing as it was with Popy Chogokin based on other manga and anime, was arguably a huge hit in the Seventies because of its innovative magnetic joints.

The most famous Takara SF Land toyline of them all would be Transformers, the result of a decades-old relationship between two storied toy companies from two different continents. Hasbro coined the term “action figure” for the original G.I. Joe in 1964 and Takara transformed Joe into Henshin Cyborg, the founding figure of Takara SF Land, in 1972. Hasbro then combined toys from two major Takara SF Land lines, Diaclone and Microman, in 1984 to create Transformers and those rebranded toys returned to Japan the following year. The line, which celebrated its 35th anniversary in 2019, has sold over 500 million toys and other products in over 130 countries.

To study Takara SF Land is to see how toy designs evolve across multiple lines over the course of decades. More broadly, it is to trace how an idea travels from one country to another, gets adapted for local needs, impacted by geopolitical events and return in a completely unrecognisable form. Delve into one Japanese toy company’s history and you will see just how Hasbro’s 12-inch G.I. Joe turned into Mego’s 3¾-inch Micronauts.

Contents

- History

- Henshin Cyborg

- Android A

- Microman

- Magne Robo

- Timanic

- Combat Joe

- Super Cyborg

- Cybercop

- Cyberman

- Metal Jack

- Gridman

- Dangarn-V

- Magnators

- Blockman

- Microman Magne Powers

- Microman LED Powers

- Microman 200X

- Cool Girl

- GenX Core

- Battle Beasts

- Beast Saga

- Neo Henshin Cyborg

- Henshin Cyborg 99

- Diaclone (1980)

- Transformers

- Transformers Zone

- Diaclone (2016)

Timelines

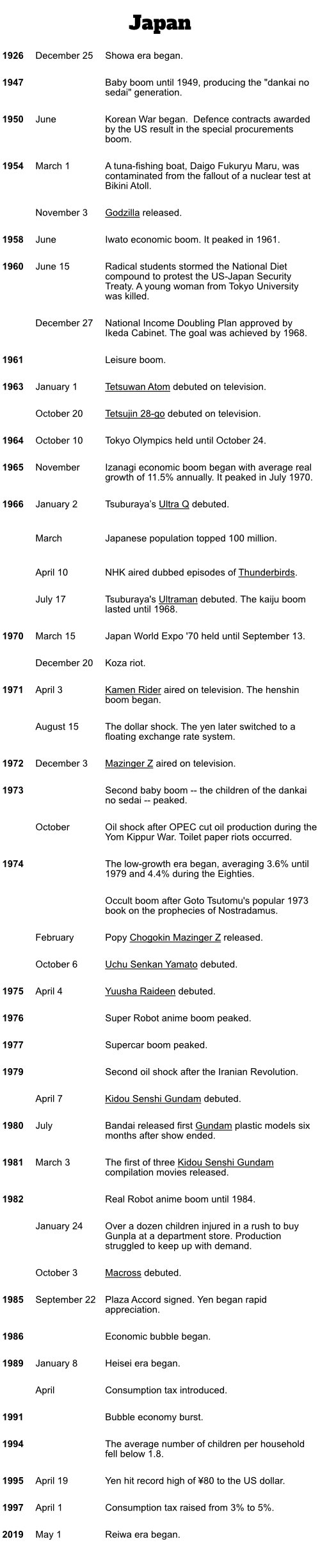

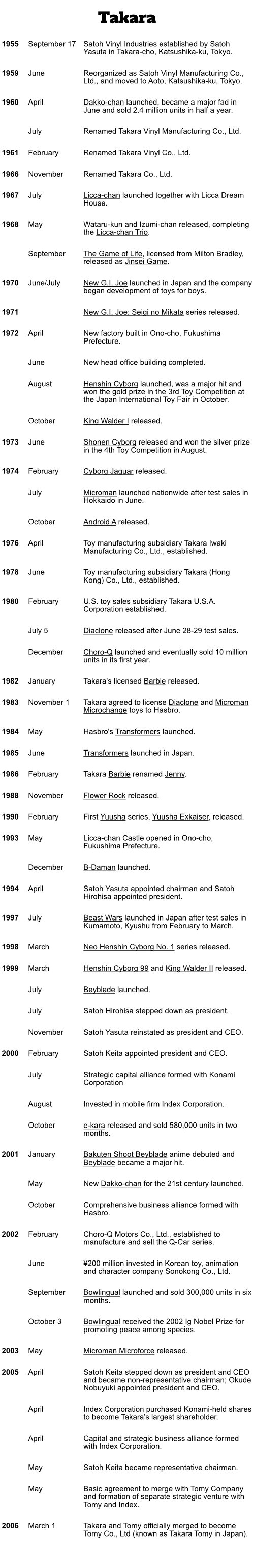

The following timelines were compiled from the Omocha Johou Net site, Takara Tomy’s corporate brochure, Takara corporate history, Henshin Cyborg history and Tomy shashi.

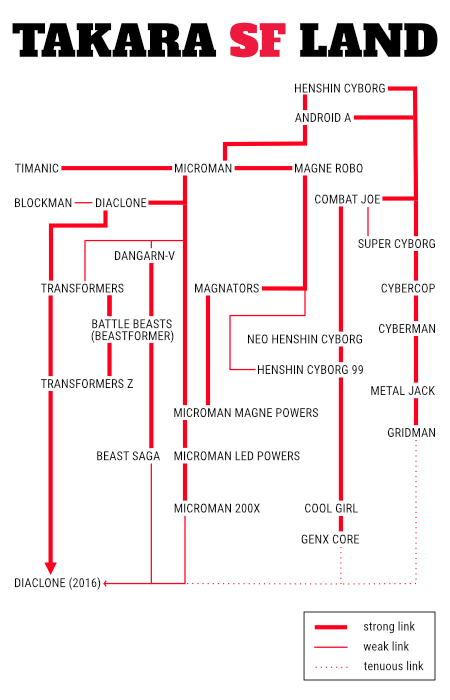

The following chart and notes were largely adapted from the fantastic 2017 Futabasha book, Takara SF Land Evolution (ISBN978-4-575-31242-3). If you’ve ever wondered why some Microman Magne Powers figures seem more Magne Robo than Microman, wondered how Takara went from Combat Joe to Cybercop or wondered what exactly inspired Battle Beasts, the book is an essential purchase.

(Click on the above image for a larger chart that’s more faithful to the source material.)

History

Takara (“treasure” in Japanese) was founded as Satoh Vinyl Industries Ltd by Satoh Yasuta in 1955 and later named after the old Tokyo neighbourhood where it started, Takara-cho. The Japanese toy company may be renowned internationally for its clever action figure designs but it was initially famous for its dolls.

Takara’s first major success was a vinyl doll named Kinobori Winky (colloquially known as Dakko-chan), which was unfortunately based on a racist golliwog caricature and even more unfortunately, inspired the company logo from 1961 to 1990. Its next hit was more wholesome. Licca-chan, a petite doll with a smaller dollhouse for smaller Japanese homes, made its debut in 1967 and quickly became the nation’s favourite.

Takara didn’t enter the action figure market until late 1969. (It wouldn’t even have a boys’ toys division until after Henshin Cyborg became a hit.) The company licensed G.I. Joe from Hasbro, had its doll designers redesign the American toy soldier’s head and rebranded the figure as New G.I. Joe for the Japanese market the following year.

The Japanese Joe initially sold well — so well that Takara was emboldened to expand the line with enemy figures. Unfortunately, these figures included SS officers complete with prominent swastikas.

There was also the matter of the war in nearby Vietnam. Japanese parents may have been increasingly uncomfortable about purchasing an American toy soldier for their kids especially when there was growing resentment over the presence of American military bases in Japan. The Koza riot, for instance, took place in 1970.

It’s not clear Takara was responding to this directly but like the American Joe, who went AWOL to lead a life of adventure, his Japanese counterpart turned his back on war. Takara first sold costumes in its Sports Series to turn the toy soldier into inoffensive sportsmen and then, through its Seigi no Mikata (Ally of Justice) series, into Japanese tokusatsu heroes like Ultraman, Mirrorman and Silver Kamen. (Ideal’s Captain Action may have been the inspiration.)

Henshin Cyborg (1972)

When New G.I. Joe’s sales slowed down, Takara reused the mould to create a clear plastic figure with mechanical innards. Henshin Cyborg 1, now recognised as the founding figure of Takara SF Land, was a major hit and a strong influence on the lines that followed. The figure had grey, silver, gold and blue colour variants.

Taking a cue from New G.I. Joe’s Seigi no Mikata series and the ongoing henshin hero boom on television, Henshin Cyborg 1 could henshin (or transform) into other characters by donning costumes. Henshin Sets sold costumes of Ultraman, Kamen Rider 1 and other popular characters of the day while Chojin Sets sold costumes based on the original character designs Birdman, Fishman and Beetleman. Additionally, Cyborg Sets sold soft vinyl weapons of various designs that could slide over the figure’s forearms.

Like New G.I. Joe, Henshin Cyborg 1 could square off against enemy figures. Thankfully, however, King Walder, a space invader, was much less controversial. King Walder (in blue, green, purple and yellow) had his own Kaijin Set costumes (Dokuro King, Satan King and Shokubutsu Kaijin) and Cyborg Set weapons.

The line was further expanded with Cyborg 2, Henshin Cyborg 1’s younger brother. Being shorter at 20cm tall, Shonen Cyborg (silver, gold and blue) couldn’t make use of his older sibling’s costumes so he had his own. He could also be upgraded with Cyborg Sets consisting of various weapons and gadgets made of hard plastic.

Cyborg Jaguar (silver, gold and blue), Shonen Cyborg’s pet leopard cub turned cyborg, followed the same pattern with Henshin Sets that transformed it into animals like a jaguar as well as Weapons Sets and Cyborg Sets containing weapons and parts upgrades. In addition to those, there were Choju Sets that turned Cyborg Jaguar into Doberman-J (Doberman Jack) and Condor-V (Condor Violence), a flying quadruped with bird-like elements.

(Takara’s designers would revisit the jaguar, doberman and condor design themes frequently over the years and the Cyborg Jaguar mould itself would be reused for Takara’s Yoroiden Samurai Trooper Byakuen-Oh a.k.a Ronin Warriors White Blaze.)

The stylish Cyborg Station CX-1 carrying case for the Cyborg figure was probably inspired by the New G.I. Joe Secret Base and James Bond’s gadgetry. This was a child-scaled attaché case which opened up to reveal a base of sorts. When placed upright with weapons and accessories attached to its various hardpoints, the Cyborg Station had a passing resemblance to the Diaclone Car Robot Battle Convoy robot maintenance dock but what’s more noteworthy is Takara would come up with some creative concepts based on secret agent attaché cases in later lines.

The greatest innovation of the Henshin Cyborg line saw Takara’s designers take the transformation concept beyond cosplay. By attaching parts from the Cyborg Rider motorcycle, sidecar, exploration car, minibike and weapon sets, Henshin Cyborg 1 could be turned from action figure into a toy motorcycle which Shonen Cyborg could ride. Almost half a century later, the Cyborg Rider remains a startling design that demonstrated the young company’s creativity and ambition. From that point on, Takara’s sci-fi toys would consistently push action figure design as far as it could go given the limitations of the era.

Some of those limitations were geopolitical in origin. Various Middle Eastern crises resulted in oil prices spiking in the early Seventies and this caused severe problems for Japan since it imported all of its oil. This naturally had a major impact on the toy industry because the price of oil affected the cost of plastic used to manufacture playthings. Henshin Cyborg, for example, required raw materials that were prioritised for daily necessities and automobiles so Takara’s Okude Nobuyuki had to convince a supplier that children all over the country were eagerly awaiting the toy. He succeeded but the oil crisis continued to be a vexing problem for the Japanese toy maker.

Android A (1974)

Originally meant to be part of the Henshin Cyborg line, Android A (Android Ace) was released in 1974 as its successor instead. Much like the Cyborg Rider, Android A took the concept of transforming beyond costumes. The 30cm-tall figure could replace its head, entire limbs and even its removable chrome-plated chest engine. There were three types of full sets: the standard Android A, the Chojin (superhuman) form and the Robot form. There were also accessory sets to turn Android A into his powered-up variant forms.

Just as Henshin Cyborg had the alien King Walder to contend with, Android A faced off against Shonen Cyborg-sized alien opponents of his own. The Aliens — the scientist Zeros, the vicious Zone and the mysterious sorcerer, Jagra — could increase their threat level with weapon sets sold separately. (The trio would be reborn as Neo Henshin Cyborg villains in the Nineties.)

The aliens could tool around in a large UFO-7 vehicle with a removable inner cockpit/vehicle. This was a substantial piece of plastic at a time when the cost of it was rising so it’s perhaps understandable Takara decided to sell these components separately.

(Japanese toy makers weren’t the only ones affected by rising costs. Denys Fisher resorted to selling scaled-down Shonen Cyborg-sized versions of various Henshin Cyborg and Android A figures for its Cyborg line in the UK.)

Takara had a big problem on its hands. The solution was to think small. In doing so, the company came up with its greatest Takara SF Land hit.

Microman (1974)

Takara designer Ogawa Iwakichi had attempted creating a smaller posable action figure as far back as the New G.I. Joe days after his superior recognised that vehicles scaled for the 12-inch toy soldier were prohibitively expensive. Ogawa gave up the effort thinking there was no way of making it viable for production but if he had succeeded, the first 3¾-inch G.I. Joe may well have been A Real Japanese Hero in the Seventies. He revisited the idea when the full impact of the oil crisis hit during the production of Henshin Cyborg and this time he succeeded after much trial and error.

Ogawa’s initial Microman figure design was clearly based on Henshin Cyborg but, being one-third of the size, various design simplifications were made. Instead of a removable clear vinyl head with a chromed cybernetic inner skull, Microman had a chromed head. Instead of a clear plastic torso with mechanical innards, Microman had a chrome-plated chest piece on a clear plastic body that tried to evoke the same effect.

What really stood out about Microman was the fact it was a 10cm figure with stunning articulation for the time. Keep in mind the Kenner Star Wars figures released a few years later only had five points of articulation. Like a Star Wars figure, Microman could move at the head, shoulders and hips but the Japanese figure also had elbow and knee joints, an O-ring waist joint (almost a decade before Hasbro’s 3¾-inch design) and even ball-jointed wrist joints.

It wasn’t just the articulation of the figures that made the Microman line extraordinary, however. The other major reason it stood out was the sheer variety of remarkable toy designs produced over the span of a decade. There were incredible bases, vehicles and robots — most of which could be taken apart and recombined with each other in new forms. The more Microman toys you had, the more possibilities you had. It was a creative and imaginative line that encouraged creative and imaginative play.

The inspiration for this was, of course, Lego. But Ogawa also revealed Microman’s Yukei Block (usually translated as Material Block) approach was meant to get Japanese boys, apparently a particularly urbane and sophisticated prepubescent set in the early Seventies who thought Lego was for babies, interested in block-style creative play.

The Yukei Block approach made block play cool by making each clearly defined “block” element representative (a Microman wing part actually looked like a wing especially when compared to how Lego bricks of that era were abstracted as one) and imbuing it with sci-fi design elements.

The connectivity between parts was based on standardised 5mm-sized pegs and ports so you could freely mix and match parts to create your own variants. (Mego’s Marty Abrams cited Microman’s construction and building play pattern as a key reason for licensing the Japanese line and rebranding it as Micronauts for the US market in 1976.)

Takara realised early on this was a key advantage and made sure kids understood this connectivity extended to interchangeability between Takara lines. The 1974 Microman and Android A catalogues provided a brief writeup of how Microman encountered Henshin Cyborg 1 and Android A, and formed an alliance to repel the alien invaders menacing Earth. The cross-line appeal of this “Victory Plan” borne of this alliance was made clear by illustrations of combinations made from Henshin Cyborg 1, Shonen Cyborg, Cyborg Weapons, Cyborg Rider, Cyborg Jaguar, Android A and Microman parts. This was arguably the moment Takara SF Land came into its own.

The most notable toy resulting from this Victory Plan crossover was the Microman Robotman. The packaging pointed out Robotman’s “helbrain” was derived from Henshin Cyborg 1’s brain and, toy-wise, the Robotman’s cockpit enabled the 10cm-tall Microman figures to interact with the 30cm figures from the Henshin Cyborg and Android A lines. The prominent “V” and “S” on Robotman were from “Victory Series” indicating it was intended to be the first of many such crossover toys. As it turned out, the Henshin Cyborg and Android A lines ended even as Microman went from strength to strength.

Microman’s success was partly attributed to the abundance of motifs and gimmicks used throughout its initial run. The Seventies fascination with mysteries and mythologies, the ancient and the alien — typified by In Search Of Ancient Astronauts — was reflected in the Japanese toyline. Speculation about alien visitors inspired the Microman storyline, Rapa Nui mo’ai and Egyptian sarcophagi inspired hibernation capsule designs, Nazca lines inspired chest designs, and so on.

The thing to remember is all this was before Star Wars, Gundam and the robot anime boom. For many a Japanese kid, Microman was their first encounter with sci-fi and the fantastical. The relative paucity of sci-fi material back then didn’t just affect fans; it was an issue for creators as well. Design Mate’s Higuchi Yuichi, who worked on Microman toy designs and packaging, recounted how there was little in the way of reference material even for designers in those days. Hayakawa’s SF Magazine was the major Japanese sci-fi publication of the day but Higuchi, not being a sci-fi fan or a military buff, turned instead to American department store catalogues. A lawn mower, for instance, inspired some of his mechanical designs.

In terms of gimmicks, Microman ran the gamut. There were rubber-band-powered plastic model vehicles, a remote-controlled vehicle, motorised robots, robot-vehicle hybrids, transforming cars, transforming robot cars, combining robots, etc.

And then there were the toys powered by magnets.

Magne Robo (1976)

It’s generally assumed Takara based the Magne Robo Koutetsu Jeeg toy on Nagai Go’s design and later reused Jeeg’s Magnemo gimmick for its Microman Titans figures but Magnemo’s origins are a little more complicated than that.

Takara’s Okude revealed Magne Robo and Microman were developed simultaneously but Magne Robo (another invention of the underappreciated Ogawa) was put on the back burner in order to focus on Microman’s product rollout. Company president Satoh Yasuta later asked TV Magazine editor-in-chief Tanaka, who was working with the toy company on the Microman manga, to come up with a similar treatment for Magne Robo and handed him the prototype. Tanaka then passed it on to Nagai who came up with the final design.

The Jeeg manga debuted in March 1975 and the Toei anime began that October. Okude noted Takara was one of the first Japanese toy makers to sponsor a television show based on its product. This was a gutsy move for the small company considering its initial reluctance to spend money advertising Microman on television for its nationwide release a few years earlier.

The investment paid off handsomely. The Jeeg toy was a major hit and the Magnemo gimmick was a major reason why. The Magnemo-powered Jeeg used magnets in the figure’s torso to connect magnetically to iron spheres affixed to limbs and other parts. (The spheres came in two diameters: the larger 11mm Magnemo-11 was used for Jeeg while the Magnemo-8 size was later used for the smaller Microman Titans figures and cheaper toys.)

The resulting articulation was superb for its time (particularly when compared to the Popy Chogokin Mazinger Z it was competing against) but on top of that, the magnetic connections meant parts could be easily attached and detached. Jeeg’s Mach Drills, for example, could be placed on Jeeg’s back or they could replace limbs. Panzeroid, Jeeg’s simple but elegant steed, could be transformed into a goofy wheeled mode politely described as a tank or combined with Jeeg to form an impressive centaur. Magnemo’s connectivity, while less expansive than the Yukei Block approach, followed the same mix-and-match play pattern that made Microman such a success.

Magnemo toys were also released by Takara licensees, Mego and GiG, and since Takara didn’t patent the gimmick, competitors quickly produced Magnemo-like toys of their own.

Takara itself reused the gimmick for its Magne Robo Gakeen and Chojin Sentai Balatack toys as well as a few other lines. Decades later, the toy company would include Magnemo joints in its revival of Microman and Henshin Cyborg to produce some of its best action figures.

Timanic (1977)

Space Traveler Timanic was a short-lived line consisting of visually impressive figures and peculiar vehicles. The Timanic 1, Timanic 2 and Timanic 3 figures had opaque armour pieces which could be removed to reveal translucent and chrome-plated cybernetic parts. At 18cm tall, the figures stood between Henshin Cyborg and Microman.

The story line, set in the distant future of 2004, was novel and perhaps befuddling for the elementary school kids who were the target audience. The Timanic were Neo Cyborg — human consciousness controlling a cybernetic body capable of withstanding the rigours of hyperspace travel. They travelled light years to battle aliens who were after Earth’s water.

(If the recurrent theme of fearsome alien aggressors with advanced technology seems overdone in Takara SF Land, consider Japan’s historical experience with the same.)

The Timanic figures included an underwhelming non-Magnemo magnet-powered gimmick: the head lit up when the figure was disassembled and combined magnetically in a variety of odd ways with the motorised Time Machine vehicles.

The Timanic 3 Deluxe figure variant set included a battery pack that enabled the same feature. Interestingly, the battery pack was largely identical to that for Takara’s Gimca FMB System diecast minicars. However, the contact widths differed so they weren’t interchangeable.

It’s perplexing Timanic didn’t make extensive use of Microman-compatible 5mm joints or Magnemo-compatible magnet joints. If there had been cross-line appeal, perhaps it would have fared better. Today, it’s largely overlooked even by Takara’s fans.

Takara’s designers, however, ever cognisant of their company’s rich heritage, would give a nod to Timanic with the Microman Magne Force Achilles, Theseus and Icurus figures in 2005.

Combat Joe (1984)

Combat Joe: Real Action Figure Series was a line of 1/6-scale military and law enforcement figures for the nascent adult collector market. Though it wasn’t quite in accordance with the 20-year-old rule, it seems safe to assume the line was aimed at Japanese men who grew up with Takara’s New G.I. Joe in the early Seventies.

Combat Joe’s inclusion in Takara SF Land seems anomalous until you consider the figures were based on the Henshin Cyborg 1 mould (which was in turn based on New G.I. Joe) with redesigned heads.

Combat Joe was notable at the time for the relative accuracy of its cloth uniforms. Oddly enough, the line also had a non-military issue Godzilla costume set. This coincided with the release of the 1984 Godzilla film (The Return of Godzilla) and the included Combat Joe figure represented the original Godzilla suit actor, Nakajima Haruo.

(Two decades later, the Microman KiguruMicroman Series Godzilla set was released to coincide with Godzilla: Final Wars.)

Super Cyborg (1987)

Super Cyborg was an unreleased line developed for overseas markets. The 20cm figure (the size of Shonen Cyborg) initially had realistic clothing like Combat Joe and was intended to have several outfits but that feature was dropped after the clothes looked baggy on the smaller frame.

The line was meant to update Henshin Cyborg but the emphasis would be on subterfuge rather than transformation. Super Cyborg was a suave business suit-clad secret agent who could replace his forearms with weapons retrieved from attaché cases. He could also make use of Container Bike, a foldable scooter, and Container Gyro, a gyrocopter, which were hidden in a container and trailer respectively. (The Microman Magne Powers Spy Heli set, which had a Microman-sized gyrocopter stored in a noodle cup, is an interesting take on this concept.) A larger trailer, which unfolded to become a playset, was also planned.

The Super Cyborg project was cancelled when Takara switched focus to the domestic market with Mashin Eiyuuden Wataru, Yoroiden Samurai Trooper (Ronin Warriors) and Dennou Keisatsu Cybercop. This was probably the result of the 1985 Plaza Accord which set in motion a complex series of events whose repercussions are still being felt in Japan today. The rapid appreciation of the yen following the signing of the accord made Japanese products less competitive in foreign markets and there was a concurrent effort by the Japanese government to spur domestic demand. Takara Tomy chairman and CEO Tomiyama Kantaro noted in the company’s 2020 annual report the Plaza Accord caused a major crisis at Tomy because the company relied on exports for most of its sales and Takara was forced to make adjustments as well.

Dennou Keisatsu Cybercop (1988)

Cybercop was Takara’s first foray into the world of tokusatsu. The Toho live-action television show looks cheesy by today’s standards but the Bit Suit action figures were phenomenal designs for the era. Takara designer Takaya Motoki revealed in the Futabasha book the cancelled Super Cyborg project served as a starting point for Cybercop’s development but there might be more to the story.

Design Mate’s Higuchi Yuichi made an extraordinary claim in a 2018 Hobby Japan Mook interview: Cybercop began as an idea for the Jenny line. Although he didn’t specify the timeframe, this would most probably have been in 1986 when Takara began preparations to rebrand its version of Barbie as Jenny after Mattel terminated Takara’s Barbie license. Higuchi’s wife suggested creating a male “fashion cyborg” for the Jenny line to make it stand apart from the other boy dolls in the market (e.g. Licca-chan’s Wataru-kun). Perhaps unsurprisingly, the “fashion cyborg” concept was deemed a little too unusual for a line of dolls but Takara’s boys’ toys designers apparently adapted the concept for Cybercop. Higuchi noted the basic details of Cybercop were more or less “fashion cyborg” aside from the head which was redesigned for the Toho show. He expressed frustration Cybercop was seen as a Robocop-derivative when the “fashion cyborg” concept predated the American movie. (It’s worth noting the tokusatsu Metal Hero series began before both Robocop and “fashion cyborg.”)

The two origin stories are not irreconcilable. The initial concept for Super Cyborg was a cyborg secret agent who could dress up in different outfits — something that could have certainly been inspired by an offbeat design concept for a fashion doll line. Furthermore, Takaya took over the Super Cyborg project (under supervision from his seniors) after many concept sketches and prototypes of the figure and a supercar had already been completed so that doesn’t rule out the possibility Super Cyborg was derived from the unused “fashion cyborg” idea and Cybercop was then inspired by the cancelled Super Cyborg project.

Regardless of its origins, Cybercop, like Super Cyborg before it, should ultimately be considered an 80s update of Henshin Cyborg. The Cyborg Weapons concept from Henshin Cyborg was updated as Cybercop’s stylish Cyber Arm and Cyber Weapon arms and accessories. These weapons could then be stored in Black Chamber cases, which were inspired by Super Cyborg’s accessory containers.

The figures were well-articulated with unique head and shoulder designs for each character and most had removable armour pieces. Lucifer Bit was the most striking of the figures and came with a remarkable assortment of cool accessories and gimmicks. The multifuctional Gigamax, in particular, was a standout design and a harbinger of complex transforming accessories to come. This was a flying drone that could also be a flight pack or shoulder-mounted heavy cannon and could split apart to become a gun/sword and shield. Being a Green Ranger-style adversary turned ally, Lucifer Bit had a menacing facemask that could be removed to reveal a face design resembling the other characters.

There was also a sleek futuristic vehicle, the Cyber Machine Blade Liner, with an odd gimmick for a very specific purpose: there were auxiliary wheels that extended sideways to enable the vehicle to drive up vertically between buildings.

There are three other things worth noting about Cybercop. First, Jupiter Bit‘s mystifying horned antenna and beetle-style wings, deployed for his underwhelming power-up form, were remnants of an abandoned insect-themed character design. Second, animal-themed support mecha — a doberman (in the tradition of Henshin Cyborg’s Cyborg Jaguar and Microman’s Dober Machine) and a bird-like Scout Falcon — were planned but not produced.

Finally, Takaya would pay tribute to the line years later in a completely unexpected format.

Cyberman (1989)

Cyberman (or Cyber 3), the follow-up to Cybercop, was developed while the Toho show was still being broadcast.

The main character would first transform into a human-sized hero and then into a giant cyborg which could then combine with combat vehicles to form a giant robot. That might seem like overkill but this was intended to improve upon Cybercop Jupiter Bit’s uninspiring power-up form.

The hero had a knight motif (with a Gridman-esque head design) and was accompanied by non-transforming android sidekicks with heavily-armed fighter and ninja design themes.

Cyberman’s dramatic shifts in scale resulted in some interesting design concepts. A large hoverboard used by the hero in human-sized form, for example, would double as the sword for his giant cyborg form.

Prototypes of the giant cyborg form, air combat vehicle and the land combat vehicle (which resembled Gridman’s God Zenon God Tank) were created and were sufficiently developed to form the giant robot. The combined form broadly resembled Gridman’s Thunder Gridman with the upper body reminiscent of Metal Jack’s Silver Jack Armor.

It’s not clear why Takara halted development on Cyberman. Cybercop fan sites report the toys sold poorly so that’s the likeliest explanation for cancelling the follow-up.

Once again, however, Takara would take ideas from an unproduced line and develop them further in later lines.

Kikou Keisatsu Metal Jack (1991)

The Metal Jack toys were produced for Sunrise’s anime series. Although it’s considered by some to be the animated sequel to Cybercop, Metal Jack began development as Outer 3, Sunrise’s own sci-fi police project.

Takara did submit Cyberman prototype samples to the animation studio for consideration and it’s also likely Metal Jack’s Lander and J Bird were influenced to some degree by Cybercop’s unproduced mecha animals.

The final Metal Jack designs clearly took inspiration from the Cyberman concept of powering-up by combining with vehicles but introduced some new elements. The Cyber Police Dog Lander, for example, could either transform into the hover bike, Jack Speeder, or combine with the main character to become the Red Jack Armor power suit.

When considered from a Henshin Cyborg perspective, Takaya noted this was akin to having a Henshin Set that could also transform into Cyborg Jaguar and Cyborg Rider.

Denkou Chojin Gridman (1993)

Gridman was Takara’s tokusatsu collaboration with Ultraman series producers, Tsuburaya Productions. The toyline took the Chojin Set power-up concept introduced in Henshin Cyborg to the very limit.

The line was essentially built around the DX Gridman figure. It had sound and light effects which were fairly unimpressive on their own but remarkably, they were activated depending on what pose the figure was put in. Raise an arm skywards, for example, and the Gridman figure would give an Ultraman-ish battle cry. (Takara’s best-selling Tetsujin 28-go FX toy had similar gimmickry.)

Takara, being Takara, went further. The Gridman figure could combine with the support robot God Zenon (itself a combination of the Thunder Jet, Twin Driller and God Tank vehicles) to form Thunder Gridman or combine with Dynadragon (a mecha dragon combination of two jets, King Jet and Dyna Fighter) to form the massive King Gridman and his Dragonic Cannon. Astonishingly, Gridman’s sound and light effects could still be activated even with all those complex combinations.

Aside from the brilliant toy engineering involved in creating all that, it’s notable how the humanoid Gridman figure was scarcely recognisable once transformed into the boxy robotic powered-up forms. This effectively transformed an Ultraman-style tokusatsu hero into a Takara SF Land-style giant robot.

Dangarn-V (1985)

Dangarn-V (Dangarn Five) was an unproduced line intended for overseas markets. Takara designer Takaya Motoki, who was shown photos of the prototypes when he joined the company in 1987, considers the line to be the missing link between Microman and Battle Beasts/BeastFormers.

At least six prototype figures were created along with several vehicles. The roughly Microman-sized figures had human and anthropomorphic animal designs. The most notable of these was the Dangarn-V Heavy Machine Gunner figure, a visored anthropomorphic serow which influenced the design of Battle Beasts Deer Stalker a.k.a. BeastFormers Big Serow.

Dangarn-V would also later inspire Takaya’s early character designs for Microman Magne Powers Arthur, Odin, Izam, Walt and Edison and is even reflected in the final design by the characters’ animal-influenced helmets.

It’s not apparent why Dangarn-V was cancelled but considering Battle Beasts consisted of smaller and simpler figures, it’s possible Hasbro, always cost-conscious, asked Takara to come up with a cheaper line for the US market.

Chojiryoku Robo Magnators (1995)

Takaya Motoki’s first entry for Takara’s internal idea contest, Takara no Takara (Treasures of Takara), was a plan to reboot Magne Robo. It won and Takaya was given the go-ahead to begin the project.

Chojiryoku Robo Magnators (as the project eventually became known) made use of powerful neodymium magnets which enabled new play patterns that were impossible for the Magnemo figures from the Seventies.

The line revolved around three Magnator figures which could pass for early design drafts for the Magne Powers Robotman Ace, Baron and Cross figures. The major difference was the Magnators were also designed to be transformable Magne Robo-style into vehicle modes. This was accomplished by transforming the Magnator’s torso and head into a Magne Core Unit and replacing the limbs with machine mode parts. Each of the Magnators had a specialised role: land, sea and air.

In addition to those, there were Power Unit Machines in the form of mecha animals with the same land, sea and air design theme: a big cat, a shark and a bird. Like the Magne Powers Magne Animals, these mecha animals were meant to power-up the Magnators by combining with them. (The art for the Magnator Aeros and the bird mecha combination had a striking resemblance to the combined form of Magne Powers Robotman Ace and Hurricane Bird.)

On top of that, a large Mechagodzilla-esque figure was designed to combine with the three Magnators to form a Super Magne Robo. One Magnator would fit in the torso and form part of the head while the other two would replace the arms.

Takaya and his colleagues were in the process of refining the Magnators designs for an anticipated anime tie-in when the Magne Robo reboot project was itself rebooted. The designers were ordered by the company president to incorporate Microman elements into the modern Magne Robo line and this eventually led to the long-overdue revival of Microman.

Gattai Senshi Blockman (1984)

While Blockman was a Diaclone offshoot, it could also be considered the ultimate realisation of the Yukei Block concept introduced a decade earlier with Microman.

In Blockman, each individual block was a 5.7cm-tall robot action figure made of plastic and diecast metal with four points of articulation and 14 5mm connection points. The smallest sets included a solitary Blockman and accessories while the larger giftsets contained over a dozen Blockman figures. The latter also included fixed-pose chromed silver figures which, at 3cm tall, were the size of Diaclone pilots (discounting the magnetic platform shoes).

By combining several Blockman figures, parts and accessories, you could construct sci-fi vehicles and larger robots. The official combinations described in the instructions, catalogue and packaging were bland but the real appeal of any Yukei Block toy is mixing and matching parts to come up with your own creations.

Sadly, the line was shortlived due to lacklustre sales. It’s a real shame because Blockman could have been the linchpin for Takara SF Land in the mid-Eighties. The line had numerous parts that could take advantage of Microman’s 5mm pegs and ports, and the vehicle and robot cockpits could accommodate Diaclone pilots. The combination of those elements also meant Blockman had crossover appeal with the first few waves of Transformers.

Takara never saw fit to revisit and update Blockman but Bandai’s Machine Robo Mugenbine was very Blockman-like and indy toy designers like Matt Doughty and Ben Mininberg have certainly taken inspiration from it.

Microman Magne Powers (1998)

Magne Powers represented the major return of Microman after being in hiatus for over a decade. On the face of it, it might have seemed a no-brainer for Takara: take a once-great, now-moribund line, update it to reflect modern trends and rub your hands gleefully as the money pours in. But it just wasn’t that simple. What might have been successful in the Showa-era Seventies might not pass muster in the Heisei-era Nineties because as times change, so do kids and their attitudes towards toys.

The major problem affecting Takara and other Japanese toy companies was demographic in nature: there were far fewer kids due to the declining birth rate. Matters were made worse because those kids were quicker to outgrow their toys and turn their attention to other amusements like videogames. As toy industry analysts of that era kept nervously pointing out, the kids were getting older younger. Aside from this “age compression” aspect affecting their already-dwindling domestic market, the Japanese toy makers also had to grapple with the fact the kids who did get toys were mainly content with figures which meant peripheral products like bases and vehicles weren’t likely to sell as well as they did in the Seventies and Eighties. If that wasn’t enough, Takara’s designers also had price restrictions to consider. Their superiors suggested keeping the toys below the 3000 yen price tag if possible since that was considered a key reason for Beast Wars’ success in Japan.

The designers had to keep all that in mind as they set about reviving Microman for a new generation. In order to keep production costs for vehicles and bases low, the line revolved around a smaller figure design. To ensure the 8cm figures interacted well with peripheral products, the designers emphasised gimmickry based on magnets. The core figure would have magnets on the feet (much like Diaclone pilots) to allow it to easily attach to metal surfaces on bases and vehicles as well as magnets on the chest and left hand to activate gimmicks on those items. Since Takara had to target a younger demographic, the figures were designed to be durable to prevent the magnets being dislodged and ingested.

(The stylish Super Microman figures, released in a later wave, ditched the chest magnet, replaced the arm magnet with a magnet on a weapon accessory and improved the articulation.)

Magnets were also a key part of the Robotman designs, some of the finest figures Takara has ever produced. Like the cancelled Magnators figures, the Robotman figures’ stronger neodymium magnets enabled more ambitious interchangeability options compared to the original Magne Robo figures.

There were, of course, obligatory nods to previous Takara SF Land lines. Some of these relatively overt. The Giant Acroyear component, AcroBeta, was immediately recognisable as an homage to the Microman Micro Robot 1 (a.k.a. Micronauts Microtron). Other references to older Takara lines were so subtle as to be barely discernible. The combination of Robotman Ace and a pair of Magne Titan JetMogura did superficially resemble Drill Jeeg; the combination of Robotman Cross and Hurricane Bird parts did make him look like he was cosplaying Death Cross; a Robotman Baron powered up with a pair of Rocket Punch parts wasn’t that far off from Emperor, the Baron Karza variant by GiG. Considering the younger designers’ penchant for callbacks to their predecessors’ work, it’s likely these faint resemblances to classic Magnemo-11 toys were intentional rather than coincidental.

There were several toys in the line that were designed to interact with both the smaller Microman and the larger Robotman figures. The Magne Animals Hurricane Bird, Magne Jaguar and Magne Cougar, for example, could either be mounts for the Microman figures or Magnemo-11 power-ups for the Robotman figures.

The traditional 5mm ports and pegs, initially downplayed in the line, were abundant in the U-Borg accessories released by Media Factory. These were school stationery items that also functioned as Microman accessories. The Microwing 10 ruler, for example, served as a flight pack, a compass doubled as a Power Sword and a pen, fittingly, was the even more powerful Unit Shell Laser.

There were also numerous 5mm connectors in the Microman Kit — mechanical creatures sold as plastic kits that could be transformed into Microman vehicles — and these kits could be combined into something that could pass for a mecha if you tilted your head to the side and squinted at it intensely for several minutes.

The centrepiece of the Magne Powers line, the Microstation base, was a combination of the classic Road Station base and a Playstation-type console. Aside from being an impressive piece of design, it was a clever way of acknowledging the major obsession of modern kids and integrating it into the toyline. The Microstation transformed between non-functional game console, flight mode and base mode, and included various gimmicks that were activated by the figures’ magnets. Its Road Station-inspired tracks could be used by the goofy Zenmain toys and those tracks could be extended with ChoroQ rails.

The initial marketing for Magne Powers played up the fact this was the Showa-era Microman fans, now adults, passing on their love for Microman to their children. However, when Takara marketing man Itagaki Kozo visited stores on release day, he discovered the older fans were purchasing the entire line-up for themselves. He went so far as to suggest Magne Powers’ initial success was partly due to the enthusiasm of these older collectors. The Studio Pierrot anime series, Chiisana Kyojin Microman, proved popular when it debuted in 1999 but toy sales soon began to stall. Itagaki attributed this to the slow rollout of bases and vehicles for the figures.

There were other factors involved, however. Takara was experiencing a lot of problems internally during this time and this would affect the development of the Magne Powers sequel as well.

Microman LED Powers (2000)

Takara was in bad shape in 1999. The company announced a loss for the half-year period ending September and it was nearly bankrupt. Satoh Hirohisa resigned as president and his father, Takara’s founder, returned briefly to save the company. It would not be an easy task. Feeling creatively stifled under the previous president, employees had left and those who remained were in low spirits.

The 2000 Microman line was developed under those conditions which explains why it was a strange mishmash of interesting new designs and desperate recycling of old ones.

The Magne Powers sequel downplayed magnets (the new figures only had them on their feet) and focused instead on LEDs. Each figure had one on its chest which was activated by a battery-powered backpack.

Perhaps anticipating the possibility a child of the new millennium might not find a light turning on and off to be a tremendously entertaining diversion, a subsequent wave introduced Secret Breast versions of the characters. Kids were invited to rub each figure’s chest vigorously to reveal a colour that indicated the secret mission the character was embarking upon. This probably would have been more suspenseful if a sticker on the back of the package didn’t give the colour away. If the figures’ colour schemes seemed murky overall, it’s because they were a nod to the old Microman Real Type toys (which were influenced by the Gunpla boom of the early Eighties).

The Shining Tector wave had the best-looking figures of the line. Perfect Shining Solomon, in particular, was a beautiful design with the gold, metallic green and translucent yellow of the figure enhanced by the translucent blue accessories.

In terms of innovation, the standouts were the Microboy sets. These were Game Boy-inspired toys that transformed between non-functional handheld game console, Robotman-like piloted mecha, vehicle and base modes. The Microman pilot figure included in each set had a modified backpack with an infrared transmitter that could flip open several panels on the Microboy. That may seem fairly underwhelming as gimmicks go but keep in mind the severe constraints the designers were working under.

These constraints were more apparent when it came to the other peripheral products. If these vehicles and bases seemed to be an awkward fit for the line, it’s because they were refurbished Transformers moulds hastily thrown into the mix. (Considering Microman contributed some noteworthy Transformers toys back in 1984, this could also be construed as Takara SF Land’s greatest brand repaying an old debt.) The 1990 Action Masters Armored Convoy Optimus Prime set was turned into the Microtrailer, the 1995 Generation 2 Laser Cycles Road Pig and Road Rocket were modified to become Micro Bikes and the 1989 Micromaster Countdown set was now the flagship item of the LED Powers line, the Micro Rocket Base. Takara was presumably forced into this course of action because of a limited development budget and the need to fill retail space reserved for the line.

The lack of funds also meant there was no anime tie-in for LED Powers so Takara had to make do with storytelling through in-package pamphlets and a manga tie-in. While this approach may have been successful for Microman in the Seventies, it did not go over well with Heisei-era kids and LED Powers fizzled out.

But even as the line ended, Takara’s situation improved under the leadership of its fourth president, Satoh Keita. The youngest son of the company founder would not only turn things around, he would take Takara to new heights. He did this partly by asking his demoralised employees, “What do you really — really — want to do?” The Microman designers’ answer to that question produced some of Takara SF Land’s most ambitious figures.

Microman 200X (2003)

When LED Powers ended in 2000, Microman seemed finished as a brand as well but Takaya Motoki was not prepared to give up on it. His plan to reboot Microman won Takara’s internal idea contest the very next year.

The “Microman 2001 Rebirth Plan” involved creating a 10cm figure with as much articulation as possible. However, the target market would now be adults rather than kids. There were several possible reasons for this change in direction: Magne Powers and LED Powers didn’t seem to resonate with Heisei-era kids, Takaya had success with the 2000 Cool Girl line aimed at older toy fans and this approach was in line with Satoh Keita’s goal of expanding Takara’s customer base.

In order to broaden Microman’s appeal, the plan also called for licensing popular characters in the beginning before eventually developing a “Takara SF World” story background aimed at adults. For some reason, Takaya was never approached to be a part of the development project but the lines resulting from his 2001 plan would eventually be collectively known as Microman 200X.

As the 2005 Microman Perfect Works book makes clear, however, the origins of the reboot predate this. Designer Ichikawa Hirofumi had been working on an 8cm Microman figure design with dramatically improved articulation in early 2000. Although it was the size of a Magne Powers figure, it had double-jointed knees, ankles and shoulders. The prototype based on this design improved the articulation even further — the elbows were now double-jointed as well.

This base body was dubbed the “Hadaka Microman” (Naked Microman) but despite the outstanding articulation, Takara had trouble deciding how to use the figure. One slightly mystifying suggestion was creating customised figures as souvenirs for local tourist spots.

In 2002, the prototype figure was reworked to become 10cm tall — about the size of the Showa-era Microman figures — but there was little desire for a simple nostalgia-driven retread of classic designs from the Seventies. After meeting with prominent Microman fans in June, Takara finalised plans to use the new figure design for a modern Microman line as well as a line of licensed characters. The emphasis would be on producing superbly articulated, gimmick-free figures with cool designs.

The initial design sketches were extraordinarily ambitious. At one stage, the designers were planning on creating a Microman-sized Neo Henshin Cyborg. This would have neatly paralleled the 1974 Microman line which was essentially Takara’s attempt at shrinking the 30cm-tall Henshin Cyborg 1 figure to a more cost-effective size.

But the 21st century version would see Takara taking the idea to the next level. The Microman-Cyborg would have a removable head that revealed a cybernetic inner skull (like Henshin Cyborg 1) and could replace its forearms with weapons (like the Cyborg Sets of old). If that wasn’t enough, there were plans to create Henshin Sets to transform the figures into characters like Dokuro King.

Most astonishing of all, the 10cm-tall Microman-Cyborg would also transform into a Microman-scaled Cyborg Rider. A fusion of action figure and vehicle, the Cyborg Rider was an ambitious design for a 30cm-tall figure in the Seventies; to attempt to do the same with a 10cm figure was mindboggling. While none of these ideas made it even to the prototype stage, it provides a clear indication of the designers’ mindset: they were intent on pushing this 10cm action figure design to the limit.

Since the Microman 200X figures were aimed at toy fans aged 15 or older, the designers were less restricted by concerns over safety and durability. Thus, the line had a lot of chrome-plated parts (which might be easily scratched by rough handling) and the accessories were relatively small and delicate. Designer Shinohara Tamotsu, being a toy fan himself, estimated each figure would be handled lightly for about two hours on the day of purchase, 2 to 3 times more in that same week before finally being placed on display.

(On the downside, the figures were perhaps a little frustrating to handle. Move a limb here and an accessory would fall off there. Reattach that part and another tiny piece would decide this would be an opportune moment to detach and find itself a hiding place. Unlike the Magne Powers and LED Powers figures, the 200X figures simply weren’t meant to be fiddled with absentmindedly.)

The first of these all-new, all-different Microman-branded lines was MicroForce. Commander, Ninja, Gunner and Spy were released in May 2003 for about 980 yen in Japan and about 5 dollars in the US. Those were remarkably low prices considering what you got. Takara did stint on packaging — MicroForce came in a flimsy plastic cannister containing a paper insert and plastic baggies for the accessories — but you forgot all about that once you had the figures in hand. The articulation for these 10cm figures were as jaw-dropping in 2003 as that for the original Microman figures must have been in 1974. Most of the joints may seem unremarkable today even on similar-sized figures but back then the MicroForce design had no real competition. A ball-jointed chest joint was simply unprecedented on a figure this size.

The superb articulation lent itself well to the Tatsunoko Fight series of licensed characters based on Takara’s 2000 Playstation fighting game. These figures used the MicroForce body but lacked the traditional Microman elements like the chromed head. This line would eventually morph into the Micro Action Series and be expanded with the goal of attracting more casual toy fans who weren’t familiar with Microman. Accordingly, Takara licensed characters from various anime, movies, comics and games.

Microman fans weren’t content simply buying figures of licensed characters, however. Takara’s Abiko Kazutami, who took charge of the Microman 200X lines after the release of MicroForce, was aware fans were customising MicroForce and Tatsunoko Fight figures to turn them into other characters and were even coming up with their own creations. Seeing the demand for Microman-sized blank figures, Takara teamed up with Toys ‘R’ Us Japan to sell the Material Force line based on the MicroForce body design. These plain, unadorned figures with unsculpted faces made a perfect base body for customising and the 499 yen asking price was very agreeable. Unsurprisingly, they immediately sold out so Takara produced more in a variety of colours.

There was a lengthy 10-month gap between the release of MicroForce and the next wave of original Microman designs, and Takara spent some of that time contemplating how to proceed. Customer survey responses suggested fans would be partial to accessories that could not only attach to the figures but could also be combined into a vehicle of some sort. There were complications, however. Market research done back when Takara was selling replicas of classic Microman figures also revealed collectors in general were less enamoured of large vehicles. (The only large Showa-era Microman mecha or vehicle to be reissued was Robotman.) The typical Japanese domicile wasn’t designed with a large action figure collection in mind and vehicles, in particular, took up a lot of space. Shinohara himself had to get rid of his G.I. Joe vehicles when he moved because he just did not have the space for them. He firmly believed Microman vehicles ought to be small, be able to combine into a more compact form like the old Armoured Machine Cosmic Fighter and Transfer Fortress vehicles, and their component parts should double as accessories for the figures.

With all that taken into account, the MicroForce follow-up should really be seen as Takara’s tentative, nervy attempt at introducing Microman 200X vehicles. MasterForce originally consisted of three figures representing land (Groundmaster Alan), sea (Divemaster Roberto) and air (Skymaster Hayate). Automaster Ryan was almost an afterthought but proved to be the most popular of the four. This was perhaps unsurprising since his futuristic bike was the best-defined vehicle design.

The success of Masterforce inspired the designers to develop the vehicle/accessory concept further for the next Microman wave. The BioMachine vehicles, little larger than the figures themselves, could be combined into an exceptionally shiny chrome-plated BioSuit mecha to take up even less space. This approach proved popular and would later lead to the Automaster Ryan-inspired Road Spartan vehicles combining into something vaguely Transfer Fortress-ish. Both these waves would also have parts that detached from the vehicles to become armour and accessories for the figures.

The Microman figure designs, meanwhile, grew incredibly diverse over the next few waves as Takara experimented with different styles. The BioMachine wave figures were notable for their beautiful chrome plating and more mechanical design. The Road Spartan wave figures, on the other hand, had minimal chrome plating and were more anime-influenced.

The Military Force figures were apparently the result of several ideas: Ichikawa’s sketch for a Soldier Microman troop builder figure, Shinohara’s idea for a mass-produced android, Abiko’s suggestion for a lightly-armed and inexpensive Acrosoldier grunt, and customer feedback requesting cheap generic troops with lots of weapons. Space Rescue, Techno Wave, Lava Planet, Virtual Task, Night Recon, Stealth Camo, Forest Hide and Sand Storm were intended to let fans easily personalise the figures by mixing and matching parts — something very much in line with Microman’s traditional Yukei Block appeal. The design had numerous 3mm ports all over the body and the body itself could be disassembled relatively easily. (The body design would later be reused for Samurai Armor Batman and other figures.)

Aside from different looks, there were different body shapes to provide even more variety. Acroyear-X2 AcroMedalg, for example, introduced the “massive” male body which added more bulk without hindering posability.

Microman 200X was also notable for its large number of female characters. Ichikawa felt older collectors would be more receptive to them compared to the young boys who were the target market for previous Microman lines so he had sketched a female body design even before the release of MicroForce. However, development only began in earnest after Abiko took charge.

The female body was shorter at 9.5cm, had a different shoulder structure, thinner arms, a tighter waist and even the screws holding the figure together were thinner and had a smaller diameter. But the designers took pains to ensure whatever changes were made didn’t sacrifice posability in any way. The thigh swivel joint, for instance, was moved closer to the knee in order to maintain the correct proportions for the lower body. Interestingly, the designers had specific poses in mind for the female figure and reworked the design to ensure the prototype was capable of those poses. The body design was then adapted for different characters. GaoGaiGar’s Swan White was noticeably more voluptuous compared to the svelte Utsugi Mikoto.

As popular as the female characters were, there was some spirited debate at Takara over the design direction. Abiko and marketer Yasuda Takahiro were initially opposed to Quanto magazine’s proposed design for Xiang-Ni, worrying that going the cute route would damage the Microman brand but as it turned out, the Quanto Zero One magazine exclusive figure proved to be so popular it influenced Takara’s own design for AcroElsa and likely the Micro Sisters as well.

The Magne Force Microman were arguably the best figures of Microman 200X. Code named “Magne Titan” during development, Achilles, Theseus, Icurus, Phobos, Atlas and Metis had striking looks, superb articulation and were, all in all, a brilliant update of the Magnemo gimmick. The use of magnetic Magnemo-8 joints for limbs meant the 2005 figures were interchangeable with the Microman Titans from 1976 but the new designs went further. The 11mm iron ball connecting the upper and lower halves of the body (unique to this series of Magnemo figures) not only provided phenomenal torso articulation for a Microman figure but the 11mm size also gave the Magne Force figures compatibility with Magnemo-11 parts from Magne Powers from the Nineties as well as Magne Robo toys from the Seventies.

Shinohara was asked to give the Magne Force figures a Titans-like mechanical design (which was the obvious direction to go) but he opted instead to differentiate the characters with unique armour pieces. Since these detachable armour pieces reminded him of Timanic, Shinohara then decided to base the final designs of Achilles, Theseus and Icurus on the obscure Takara SF Land line.

The designers also experimented with different materials for the 200X line. The KiguruMicroman figures, for example, came with soft vinyl monster costumes while the Thunderbirds figures had cloth costumes.

Not every experiment was an overwhelming success. AcroPhantom‘s coat, for example, impeded posability despite being made of more pliable material. More disappointingly, the use of translucent plastic for some figures’ elbows and ankles sometimes resulted in those joints cracking or breaking outright while posing the figures. But then attempting the ambitious with a 10cm figure was always going to involve taking some risks and not every gamble pays off.

Satoh Keita would understand that well enough. By 2005, his risk-taking, go-with-the-gut management style — a marked contrast to his older brother’s stolid and stifling leadership — led to heavy losses after he made one gamble too many in his bid to turn Takara into a “life entertainment company.” He was forced by Konami, Takara’s biggest shareholder, to relinquish the presidency but his risk-taking didn’t stop there. As Takara’s chairman, he approached mobile company Index to purchase Konami’s shares and then broached the idea of a merger with Tomy. The negotiations between the two toy makers were brief but heated. It’s telling Satoh had to be repeatedly reminded by photographers to smile during the press conference announcing the merger because the terms were not favourable for Takara. Indeed, the merger would be deemed by some to be a de facto bailout. The merged company would be known as Takara Tomy domestically and Tomy internationally as the latter was adjudged to have more brand recognition outside Japan. The merger was clearly one last roll of the dice for Satoh but the goal may simply have been to save Takara, the company founded by his father in 1955 and helmed by his family for half a century.

It would be overstating matters to assert Takara’s fate was intertwined with that of Microman. For one thing, Microman didn’t show up until well after the company had major hits like Licca-chan, and moreover, the brand was on hiatus for most of the Eighties and Nineties as Takara focused on Transformers and the Brave series. It is possible, however, to make a case Microman’s fate was intertwined with that of the Satoh family. Takara’s founder, Satoh Yasuta, encouraged his designers to improvise and it was during his tenure that Takara turned the 30cm Henshin Cyborg into a 10cm Microman to great success even as the full impact of the oil crisis hit Japan. His eldest son, Hirohisa, ordered the revival of Microman during the Heisei era which resulted in Magne Powers and LED Powers. And it’s doubtful the groundbreaking Microman 200X line would have been approved without the impulsive youngest son, Keita, at the helm. It’s therefore fitting Microman slowly came to an end as the Satoh family lost influence once Takara became subsumed in Takara Tomy.

Microman 200X represented the last Microman figures recognisable as such released by Takara. As the last hurrah for the legendary brand, it did reasonably well and there were certainly stellar designs produced during that run. The question of why it ended is an interesting one. Did it simply run out of steam like most toylines eventually do or was it a casualty of the post-merger reorganisation? Whatever the reason, it seems fairly evident Takara Tomy doesn’t rate Microman very highly given the company’s indifference to the line’s 40th anniversary in 2014.

Yet it’s hard to believe the influential line is completely done with the 50th anniversary approaching. Considering how well the Diaclone reboot is doing as a premium-priced collector’s line, it’s possible Microman may return in the near future in a new form.

Cool Girl (2000)

Cool Girl was Takara’s attempt at merging dolls for girls and action figures for boys with the aim of creating 1/6-scale cool and sexy figures targeting the adult collector. That was unusual in itself but the project’s origins were even more startling: it began as an idea for a military version of Jenny, Takara’s fashion doll. To fully appreciate just how absurd that was, it’s necessary to look at Jenny’s history.

While Takara is usually associated with Hasbro when it comes to partnerships with American toy makers, the Japanese company once had a working relationship with Mattel. Barbie, Mattel’s crown jewel, was originally manufactured in Japan but the doll didn’t dominate the Japanese market. In fact, Mattel withdrew from the Japanese market a few years after Takara released Licca-chan in 1967. By 2017, Takara had sold over 60 million Licca-chan dolls.

Although it’s tempting to attribute Licca-chan’s popularity solely to the fact it was a Japanese doll by a Japanese toy maker geared towards the Japanese market, the story is a little more complicated than that. Takara initially intended to create a portable dollhouse for Mattel’s Barbie and Ideal’s Tammy but realised Japanese rooms wouldn’t have much space for a dollhouse scaled for American dolls. A smaller dollhouse required a smaller doll so Takara designed the 21cm-tall Licca-chan.

Licca-chan’s features, with a side-glance and an ambiguous expression, were also said to be more appealing to Japanese sensibilities. But Licca, the character, wasn’t purely Japanese. She was biracial (the prototype doll was named after Takami Emiri, a mixed-race child model) and her fashion sense reflected the Japanese fascination with all things European and American. That said, she was undeniably a product of her culture. Her manga-inspired big eyes — an artifact of Tezuka Osamu’s obsession with Walt Disney — marked her as such. The Japanese doll, in its fusion of East and West, made the West appealing to Japanese girls in a way Barbie did not.

Acknowledging Takara’s dominance of the Japanese doll market, Mattel licensed Barbie to Takara in 1980. Just as Takara localised G.I. Joe with New G.I. Joe, the Japanese toy company altered the American fashion doll for its domestic market. After spending 19 months and 100 million yen during development, Takara’s Barbie, with a rounder face and bigger eyes, was released in 1982. The fashion doll was targetted at upper elementary school girls and nicely complemented Takara’s own Licca-chan, which was popular with younger girls.

In 1986, Mattel and Takara’s doll partnership came to an end, as these things tend to do, over giant robots. Mattel had a sneaking suspicion Takara was more invested in selling Transformers than selling Barbie because Takara reportedly sold 26 million dollars’ worth of Barbie dolls in 1984 and sold 165 million dollars’ worth of Transformers to Hasbro that same year.

There were other reasons for Mattel to believe the Japanese company was less than fully committed to selling Mattel toys. For instance, Takara hadn’t bothered getting the Masters of the Universe cartoon aired on Japanese television and Mattel believed MOTU needed the cartoon to sell the toys. (Takara, for its part, had had a lot of success with Takara SF Land lines that sold without a media tie-in.) Mattel was also nervous Takara’s relationship with Hasbro would lead to trade secrets being leaked.

However, the likeliest reason for the tensions between the two companies may have been Takara’s reluctance to set up a joint venture company with Mattel to sell Barbie in Japan because the first thing Mattel did when it abruptly terminated the partnership with Takara was to set up a joint venture company with Takara’s major competitor, Bandai, to sell Barbie in Japan.

Takara promptly filed a lawsuit alleging the Ma-Ba (Mattel-Bandai) Barbie, which also had a rounder face and bigger eyes, was a little too similar to its version of Barbie. (Mattel, for its part, has a long history of thoroughly entertaining lawsuits involving Barbie.) The upshot of all this is Takara later rebranded its version of Barbie as Jenny and continued selling the doll.

So, when Takara’s designers proposed creating a military version of Jenny, picture a beaming Barbie (with a rounder face and bigger eyes) brandishing an accurately modelled assault rifle.

One of the reasons Takara attempted this unusual project was the overseas market for 12-inch figures aimed at adult collectors was growing at that time. Companies like Dragon, 21st Century and BBi, surpassing ancient standards set by Hasbro with G.I. Joe, were producing 1/6-scale figures with improved articulation and detail. After analysing those figures, Takara must have been reasonably confident it could raise standards even further given its experience with dolls and action figures in that scale. (Combat Joe, a 1/6-scale military figure line aimed at the adult collector market, was released back in 1984.)

Although Takara initially planned to create a doll with a military theme that could also use the clothes, shoes and accessories of its other dolls, the company quickly switched focus to creating an original 1/6-scale female figure aimed at adults. The overall design concept was a figure that was cool rather than cute, one more likely to have a handgun rather than a handbag.

In terms of figure design, the Cool Girl body was intended to be a movable statue — a depiction of the human form that looked good on display but with sufficient articulation for dynamic poses. The inevitable problem that arose was a realistic depiction of the human form would preclude unsightly joints making it little more than a statue whereas a superbly articulated figure would look like a cyborg with joints, hinges, rivets, screws and seams everywhere.

Takara briefly considered a seamless skin over wire internals — a method used for some dolls back then — but the technology was deemed insufficiently developed for the company’s purposes. It was also a little too suggestive of a bendy figure.

(Companies like Phicen/TBleague have since come up with some absolutely stunning 1/6-scale seamless figures using a metal skeleton.)

Takaya Motoki, who was responsible for the figure designs, character backgrounds and story setting for the line, considers the Cool Girl series to be the ultimate challenge for him as a toy designer as it required the sewn clothes and rooted hair common in dolls along with the sculpting and articulation of action figures.

His first challenge was getting a prototype ready. Development took place around 1999 — right about the time Takara was experiencing a lot of internal issues. (This would also affect the development of the company’s other 2000 lines like Microman LED Powers and Transformers Car Robot.) Takaya, without much of a product development budget, had to come up with the prototype himself. He even taught himself sewing after buying a book on handmade doll dresses in order to create clothes for the prototype.

Takaya’s solution for covering up the Cool Girl figure’s joints was a form-fitting catsuit — an idea with origins dating back to 1987 when he worked on a swimsuit for the cancelled Super Cyborg project. (The catsuit for the first Cool Girl figure, CG-01 Ice, was blue in tribute to Super Cyborg.) To avoid using screws, the figure was put together with ultrasonic welding.

The prototype designs were unveiled at the 2000 Tokyo Toy Show and the first three figures, Ice, Ash and Raven, were released that November. These were well received and sold well both in Japan and overseas. Encouraged, Takara expanded the line with male figures and even a villain.

Cool Girl was divided into two sublines: the first was based on original character designs while the other was based on licensed characters reinterpreted in the Cool Girl style. (Takaya would later propose taking the same approach for his Microman 2001 Rebirth Plan which eventually led to Microman 200X.)

On the face of it, Cool Girl seemed to have little to do with Takara SF Land. However, close inspection would reveal some interesting connections. The X-Borg (Cross-Borg) male figures, for example, were completely unrecognisable Neo Henshin Cyborg figures. Takaya would describe these figures — X-01 Guard of CG, X-02 Burai-Maru and X-03 Gekiryu-Maru — as his take on Henshin Cyborg. The figures had improved ankle articulation but more interestingly, their accessories were interchangeable with those for Neo Henshin Cyborg. (In another nod to Takara SF Land, the background story for X-01 namedropped Android A.)

Meanwhile, the CG-13 V.I.S. (Violent Interception Squad) Codename: Eris figure paid tribute to Cybercop (among other things). The figure was released on October 2, 2008 — the 20th anniversary of the Toho show’s debut — and the Battle Integration Trooper Suit armour and Fire Slugger II weapon were references to Cybercop’s Bit Suit armour and Cyber Weapon Fire Slugger.

Like many other Takara SF Land properties, Cool Girl was released without a media tie-in at the outset. Takaya, however, slowly developed the storyline and world setting as figures were released. The Cool Girl characters were part of Cardinal Garrison, an organisation which traces its history all the way back to a group of medieval female knights. Their task was to combat global conspiracies propagated by that dastardly organisation, XIXOX (Sixox).

Like many other Takara SF Land properties, Cool Girl had a media tie-in once the line developed a following. Konami, then Takara’s largest shareholder, released a videogame in 2004 to great indifference.

Despite that, the Cool Girl series lasted for 11 years, making it, somewhat improbably, the longest-running Takara SF Land line after Transformers.

GenX Core (2006)

GenX Core was a series of 1/6-scale male action heroes based on the GC Body, a “next generation core” body design. It was described by designer Takaya Motoki as Takara’s fourth generation 12-inch male action figure design. (Assuming Henshin Cyborg 1 was the first, Neo Henshin Cyborg 1 and Cyborg 99 would be generations 2 and 3.)

If GenX Core seems a particularly awkward name for a series of 1/6-scale figures, it’s probably the result of desperate scrambling to come up with something that would have “GC” for initials. Takaya would later deadpan in an interview it’s purely coincidental the acronyms for Cool Girl and GenX Core mirrored each other.

Unlike the Cool Girl series, though, the GenX Core lineup consisted solely of licensed characters. The overarching goal for the line was to achieve such a level of realistic detail that a photograph of the 12-inch figure would look like a real person wearing that outfit.

The project was a Cool Girl spin-off that was conceived when Takaya was consulting with Oshii Mamoru, the writer and director of Kerberos Saga, during the development of the Washio Midori Cool Girl figure. Oshii expressed a desire to see a male version of the Protect Gear with the same level of detail and quality. Instead of a one-off figure, Takaya proposed a series of figures to showcase the history of the Protect Gear as a way of justifying creating multiple variants.

Although the Protect Gear figure was first GenX Core project to be worked on, it ended up being released after the Batman Begins in GC figure due to Takaya’s commitment to getting the details on the Protect Gear figures right. The heat vents on the MG-34’s barrel jacket alone apparently required an expensive six-way slide mould.

The Protect Gear figures sold well despite the higher price tag but the GenX Core series itself was relatively short-lived.

Battle Beasts (1986)

Battle Beasts was a Takara-developed line of cheap collectible figures that was first released in the US by Hasbro in 1986 before returning to its country of origin as Beastformer the following year. It was initially marketed in Japan as a Transformers spin-off. In addition to Battle Beasts’ Wood, Fire and Water heat rub symbols, the Beastformer figures were also designated as Cybertron or Destron on the Transformers-influenced Japanese packaging and the characters even appeared in an episode of Transformers: The Headmasters.

In terms of design, however, Beastformer’s main connection to Takara SF Land was the cancelled Dangarn-V project which also featured armed and armoured anthropomorphic animals. It’s worth noting the 5cm Beastformer figures only had swivel joints at the shoulders which made them smaller, less posable and thus cheaper than the Dangarn-V figures would have been. A kid could quickly amass a veritable army of the 200 yen Beastformer figures with a weekly allowance and could refine that collection by trading with others to get specific figures with specific symbols.

Also noteworthy was the fact the Battle Beasts line appeared in the US shortly after M.U.S.C.L.E. (Millions of Unusual Small Creatures Lurking Everywhere), another Japanese toyline repackaged by an American company. The Mattel line was originally released by Bandai in Japan as Kinkeshi in 1983 to tie in with the popular wrestling anime, Kinnikuman. Mattel simply grabbed the rubbery figures, ignored the manga and anime storylines and then partnered with Ogilvy & Mather to create ads to market the line.

The precursor to both Beastformer and Kinkeshi was the supercar-shaped rubber eraser called keshigomu which was popular during the supercar craze in the Seventies. The craze began with the publication of Circuit no Ookami (Circuit Wolf) in 1975 and peaked in 1977 with the release of the movie based on the racing manga. The supercar keshigomu were obtained through gacha gacha vending machines for a mere 20 yen which made them appealing to kids who couldn’t afford a plastic kit or diecast scale model of their favourite supercar. The added bonus was the 3cm-long keshigomu could be stored in a pencil case and taken to school. These rubber racers were actually rubbish at erasing and were used instead as playthings. Some of them even had janken symbols on the underside — a more traditional approach to resolving disputes compared to Beastformer’s Wood, Fire and Water symbols.

Takara would later release its own Beastformer-themed keshi in the form of pencil-toppers. They were done in the Super Deformed style, were even smaller than the Beastformer figures, had no articulation whatsoever yet retained the heat rub symbols.

The Beastformer line was expanded further with vehicles and mobile fortresses. This was more in the spirit of Takara SF Land properties like Diaclone which emphasised diorama-style play combining figures, vehicles and playsets. The Beastformer Wood Beetle forest station, for example, transformed from beetle mode to a base that included a capture claw and a prison cell aside from the obligatory weapon emplacements. The Beastformer vehicles, meanwhile, had pullback motors and a mouth-chomping action.

The 250 yen Laser Beasts (known as Shadow Warriors in the US where it had a limited release), which came out towards the end of the line, replaced the heat rub symbols with an orb on the chest that revealed hidden symbols when held up to a light source. Their Battler Cruiser vehicles were significantly less impressive than their predecessors indicating perhaps Takara recognised interest in the line was waning.

Neither Battle Beasts nor Beastformer were wildly successful but someone pays tribute to them every once in a while and Takara Tomy would eventually reboot Beastformer 25 years later.

Beast Saga (2012)

After spending a decade working on the Cool Girl line, Takaya Motoki switched to the boys’ toys division to remake Battle Beasts/Beastformer. This was a return to basics of sorts for the designer because when he joined Takara in 1987 he did his on-the-job training working on prototype drawings for the last wave of Laser Beasts.